Star-starved galaxies fill the cosmos

Not all galaxies sparkle with stars. Galaxies as wide as the Milky Way but bereft of starlight are scattered throughout our cosmic neighborhood. Unlike Andromeda and other well-known galaxies, these dark beasts have no grand spirals of stars and gas wrapped around a glowing core, nor are they radiant balls of densely packed stars. Instead, researchers find just a wisp of starlight from a tenuous blob.

“If you took the Milky Way but threw away about 99 percent of the stars, that’s what you’d get,” says Roberto Abraham, an astrophysicist at the University of Toronto.

How these dark galaxies form is unclear. They could be a whole new type of galaxy that challenges ideas about the birth of galaxies. Or they might be outliers of already familiar galaxies, black sheep shaped by their environment. Wherever they come from, dark galaxies appear to be ubiquitous. Once astronomers reported the first batch in early 2015 — which told them what to look for — they started picking out dark denizens in many nearby clusters of galaxies. “We’ve gone from none to suddenly over a thousand,” Abraham says. “It’s been remarkable.”

This haul of ghostly galaxies is puzzling on many fronts. Any galaxy the size of the Milky Way should have no trouble creating lots of stars. But it’s still unclear how heavy the dark galaxies are. Perhaps these shadowy entities are failed galaxies, as massive as our own but mysteriously prevented from giving birth to a vast stellar family. Or despite being as wide as the Milky Way, they could be relative lightweights stretched thin by internal or external forces.

Either way, with so few stars, dark galaxies must have enormous deposits of unseen matter to resist being pulled apart by the gravity of other galaxies.

Astronomers can’t resist a good cosmic mystery. With detections of these galactic oddballs piling up, there is a push to figure out just how many of these things are out there and where they’re hiding. “There are more questions than answers,” says Remco van der Burg, an astrophysicist at CEA Saclay in France. Cracking the code of dark galaxies could provide insight into how all galaxies, including the Milky Way, form and evolve.

Compound eye on the sky

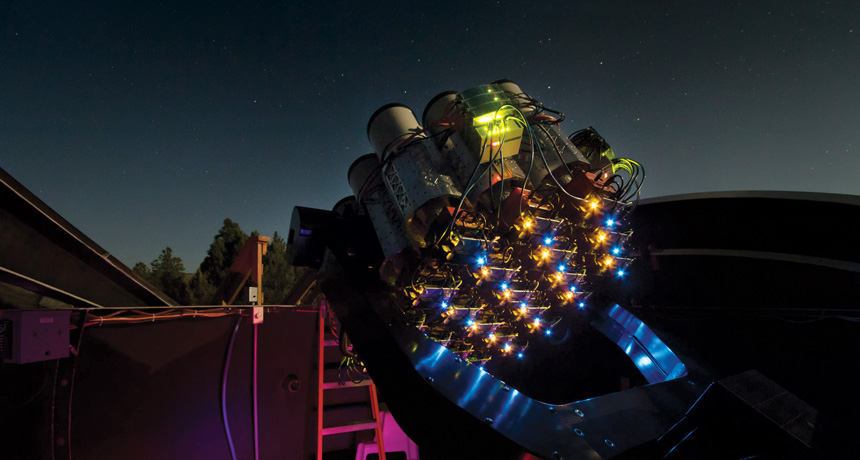

Telescopes designed to detect faint objects have revealed the presence of many sizable but near-empty galaxies — officially known as “ultradiffuse galaxies.” The deluge of discoveries started in New Mexico, with a telescope that looks more like a honeycomb than a traditional observatory. Sitting in a park about 110 kilometers southwest of Roswell (a city that has turned extraterrestrials into a tourism industry), the Dragonfly telescope consists of 48 telephoto lenses; it started with three in 2013 and continues to grow. The lenses are divided evenly among two steerable racks, and each lens is hooked up to its own camera. Partly inspired by the compound eye found in dragonflies and other insects, this relatively small scope has revealed dim galaxies missed by other observatories.

The general rule for telescopes is that bigger is better. A large mirror or lens can collect more light and therefore see fainter objects. But even the biggest telescopes have a limitation: unwanted light. Every surface in a telescope is an opportunity for light coming in from any direction to reflect onto the image. The scattered light shows up as dim blobs, or “ghosts,” that can wash out faint detail in pictures of space or even mimic very faint galaxies.

Large dark galaxies look a lot like these ghosts, and so went unnoticed. But Dragonfly was designed to keep these splashes of light in check. Unlike most conventional professional telescopes, it has no mirrors. Precision antireflection coatings on the lenses keep scattered light to a minimum. And having multiple cameras pointed at the same part of the sky helps distinguish blobs of light bouncing around in the telescope from blobs that actually sit in deep space. If the same blob shows up in every camera, it’s probably real.

“It’s a very clever idea, very brilliant,” says astronomer Jin Koda of Stony Brook University in New York. “Dragonfly made us realize that there is a chance to find a new population of galaxies beyond the boundary of what we know so far.”

In spring 2014, researchers pointed Dragonfly at the well-studied Coma cluster, a conglomeration of thousands of galaxies. At a distance of about 340 million light-years, Coma is a close, densely packed collection of galaxies and a rich hunting ground for astronomers. A team led by Abraham and astronomer Pieter van Dokkum of Yale University was looking at the edges of galaxies for far-flung stars and stellar streams, evidence of the carnage left behind after small galaxies collided to build larger ones.

They were not expecting to find dozens of galaxies hiding in plain sight. “People have been studying Coma for 80 years,” Abraham says. “How could we find anything new there?” And yet, scattered throughout the cluster appeared 47 dark galaxies, many of them comparable in size to the Milky Way — tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of light-years across (SN: 12/13/14, p. 9). This was perplexing. A galaxy that big should have no problem forming lots of stars, van Dokkum and colleagues noted in September in Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Hidden strength

Even more surprising, says Abraham, is that those galaxies survive in Coma, a cluster crowded with galactic bullies. A galaxy’s own gravity holds it together, but gravity from neighboring galaxies can pull hard enough to tear apart a smaller one. To create sufficient gravity to survive, a galaxy needs mass in the form of stars, gas and other cosmic matter. In a place like Coma, a galaxy needs to be fairly massive or compact. But with so few stars (and presumably so little mass) spread over a relatively large space, dark galaxies should have been shredded long ago. They are either recent arrivals to Coma or a lot stronger than they appear.

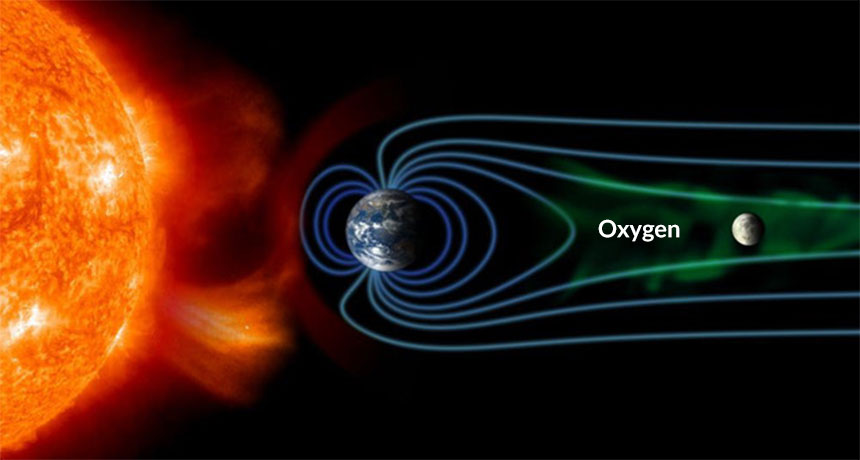

From what researchers have learned so far, dark galaxies seem to have been lurking for many billions of years. They are located throughout their home clusters, suggesting that they’ve had a long time to spread out among the other galaxies. And the meager stars they have are mostly red, indicating that they are very old. With this kind of longterm survival, dark galaxies probably have a hidden strength, most likely due to dark matter.

All galaxies are loaded with dark matter, a mysterious substance that reveals itself only via gravitational interactions with luminous gas and stars. Much of that dark matter sits in an extended blob (known as the halo) that reaches well beyond the visible edge of a galaxy. On average, dark matter accounts for about 85 percent of all the matter in the universe. Within the central regions of the dark galaxies in Coma, dark matter must make up about 98 percent of the mass for there to be enough gravity to keep the galaxy intact, van Dokkum and colleagues say. Dark galaxies appear to have similar fractions of dark matter focused near their cores as the Milky Way does throughout its broader halo.

Astronomers had never seen such a strong preference for dark matter in galaxies so large. The initial cache of galactic enigmas lured a slew of researchers to the hunt. They pored over existing images of Coma and other clusters, looking for more dark galaxies. These galaxies are so faint that they could easily blend in with a cluster’s background light or be mistaken for reflections within a telescope. But once the galaxy hunters knew what to look for, they were not disappointed — those first 47 were just the tip of the iceberg.

Looking at old images of Coma taken by the Subaru telescope in Hawaii, Koda and colleagues easily confirmed that those 47 were really there. But that wasn’t all. They found a total of 854 dark galaxies, 332 of which appeared to be roughly the size of the Milky Way (SN: 7/25/15, p. 11). They calculated that Coma could harbor more than 1,000 dark galaxies of all sizes — comparable to its number of known galaxies. Astronomer Christopher Mihos of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland and colleagues, reporting in 2015 in Astrophysical Journal Letters, found three more in the Virgo cluster, a more sparsely populated but closer gathering of galaxies that’s a mere 54 million light-years away.

In June, van der Burg and collaborators reported another windfall in Astronomy & Astrophysics. Using the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii, they measured the masses of several galaxy clusters. Taking a closer look at eight clusters, all less than about 1 billion light-years away, the group found roughly 800 more ultradiffuse galaxies.

“As we go to bigger telescopes, we find more and more,” says Michael Beasley, an astrophysicist at Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain. “We don’t know how many there are, but we know there are a lot of them.” There could even be more dark galaxies than bright ones.

Nature vs. nurture

What dark galaxies are and how they formed is still a mystery. There are many proposals, but with so little data, few conclusions. For the vast majority of dark galaxies, researchers know only how big and how bright each one is. Three so far have had their masses measured. Of those, two appear to have more in common masswise with some of the small galaxies that orbit the Milky Way, while the third is as massive as our galaxy itself — roughly 1 trillion times as massive as the sun.

A dark galaxy in the Virgo cluster, VCC 1287, and another in Coma, Dragonfly 17, each have a total mass of about 70 billion to 90 billion suns. But only about one one-thousandth of that or less is in stars. The rest is dark matter. That puts the total masses of these two galaxies on par with the Large Magellanic Cloud, the largest of the satellite galaxies that orbit the Milky Way. But focus on just the mass of the stars, and the Large Magellanic Cloud is about 35 times as large as Dragonfly 17 and roughly 100 times as large as VCC 1287.

A galaxy dubbed Dragonfly 44, however, is another story. It’s a dark beast, weighing about as much as the entire Milky Way and made almost entirely of dark matter, van Dokkum and colleagues report in September in Astrophysical Journal Letters. “It’s a bit of a puzzle,” Beasley says. “If you look at simulations of galaxy formation, you expect to have many more stars.” For some reason, this galaxy came up short.

The environment may be to blame. A cluster like Coma grows over time by drawing in galaxies from the space around it. As galaxies fall into the cluster, they feel a headwind as they plow through the hot ionized gas that permeates the cluster. The headwind can strip gas from an incoming galaxy. But galaxies need gas to form stars, which are created when self-gravity crushes a blob of dust and gas until it turns into a thermonuclear furnace. If a galaxy falls into the cluster just as it is starting to make stars, this headwind might remove enough gas to prevent many stars from forming, leaving the galaxy sparsely populated.

Or maybe there’s something intrinsic to a galaxy that turns it dark. A volley of supernovas or a prolific burst of star formation might drive gas out of the galaxy. Nicola Amorisco of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Garching, Germany, and Abraham Loeb of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass., suggest that ultradiffuse galaxies start off as small galaxies that spun rapidly as they formed. All galaxies rotate, but perhaps dark galaxies are a subset that twirl so fast that their stars and gas have spread out, turning them into diffuse blobs rather than star-building machines.

To test these and other ideas, astronomers are focused on two key pieces of information: the masses of these galaxies and their locations in the universe. Mass can help researchers distinguish between formation scenarios, such as whether or not dark galaxies are failed Milky Way–like behemoths. A survey of other locales would indicate whether dark galaxies are unique to big clusters such as Coma, suggesting that the environment plays a role in their creation. But if they turn up outside of clusters, isolated or with small groups of galaxies, then perhaps they’re just born that way.

There’s already a hint that dark galaxies depend more on nature than nurture. Yale astronomer Allison Merritt and colleagues reported in October online at arXiv.org that four ultradiffuse galaxies lurk in a small galactic gathering about 88 million light-years away, indicating that clusters aren’t the only place dark galaxies can be found. And van der Burg, in his survey of eight clusters, found that dark galaxies make up the same fraction of all galaxies in a cluster regardless of cluster mass — at least, for clusters weighing between 100 trillion and 1 quadrillion times the mass of the sun. About 0.2 percent of the mass of the stars is tied up in the dark galaxies. Since all eight clusters host roughly the same relative number of dark galaxies, that suggests that there is something intrinsic about a galaxy that makes it dark, van der Burg says.

What this all means for understanding how galaxies form is hard to say. These cosmic specters might be an entirely new entity that will require new ideas about galaxy formation. Or they could be one page from the galaxy recipe book. Timing, location and luck might send some of our heavenly neighbors toward a bright future and force others to fade into the background. Perhaps dark galaxies are a mixed bag, the end result of many different processes going on in a variety of environments.

“I see no reason why the universe couldn’t make these things in many ways,” Abraham says. “Part of the fun over the next few years will be to figure out which is in play in any particular galaxy and what sort of objects the universe has chosen to make.”

What is clear is that as astronomers push to new limits — fainter, farther, smaller — the universe turns up endless surprises. Even in Coma, a locale that has been intensively studied for decades, there are still things to discover. “There’s just a ton of stuff out there that we’re going to find,” Abraham says. “But what that is, I don’t know.”