Washington urged to keep promise on Taiwan question

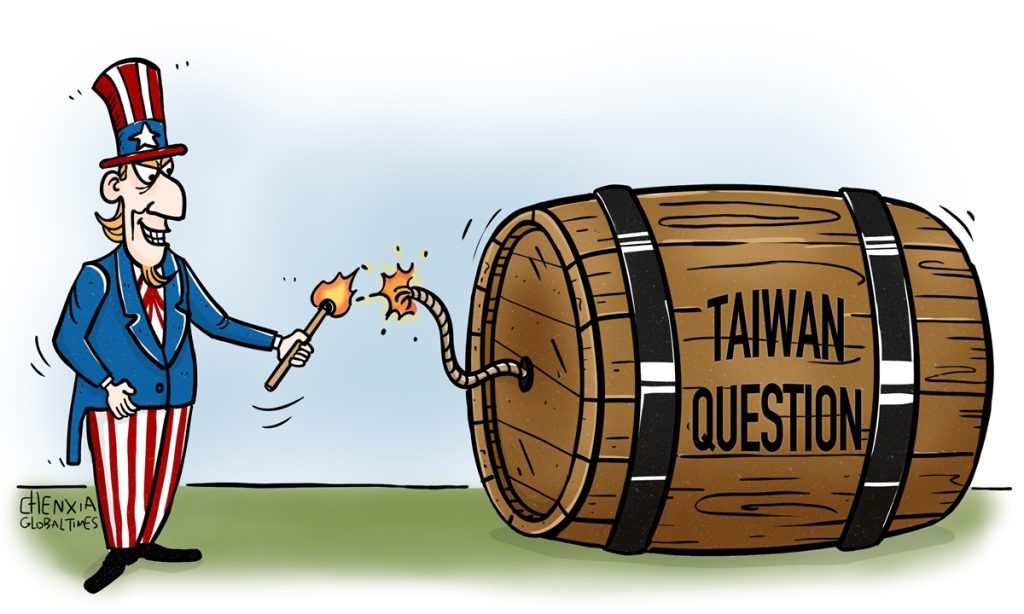

China's Foreign Ministry on Thursday urged the US to abide by the one-China principle, stop sending wrong signals to Taiwan secessionists, and refrain from interfering in the Taiwan's regional leader election in any form, after reports disclosed that the Biden administration will dispatch a delegation comprised of former senior officials to the island of Taiwan shortly after the island's regional leader election to be held on Saturday.

Chinese experts noted that the US' scheme would be destructive to China-US relations, and is highly likely to trigger countermeasures from the Chinese side, which has reiterated the core significance of the Taiwan question.

Citing people familiar with the plan, the Financial Times (FT) said in a Wednesday report that the White House has tapped James Steinberg, a former Democratic deputy secretary of state, and Stephen Hadley, a former Republican national security adviser, to lead the bipartisan delegation to Taiwan island.

The FT report said that the purpose of sending the delegation is to ensure Washington was "communicating clearly" with the winning and losing candidates about US policy and the "uniqueness of the unofficial relationship" between the US and Taiwan island.

The Associated Press (AP) said sending the delegation is the "most effective way" to engage the newly-elected authorities and convey US policy.

One senior administration official said that the delegation "will convey the importance of ties" between the US and Taiwan island and also reiterate Washington's "one-China policy," CNN reported, noting that exact composition of the delegation was still being determined, per senior administration officials it reached.

"Taiwan is an inalienable part of China. China always firmly opposes any form of official exchanges between the US and Taiwan authorities," Mao Ning, a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson said.

The US side should earnestly abide by the one-China principle, prudently and properly handle the Taiwan question, stop sending any wrong signals to Taiwan secessionists, and refrain from interfering in the Taiwan regional elections in any form, so as to avoid causing serious damage to China-US relations and peace and stability across the Taiwan Straits, Mao said.

She added that China will take resolute and forceful measures to safeguard national sovereignty and territorial integrity.

Lü Xiang, an expert on US studies at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times that the US releasing such a message a few days before the Taiwan regional election is a move apparently aimed at appeasing secessionists on the island, and encouraging voters "not to be afraid to support secessionists."

US tricks cannot change the overall situation of the Chinese mainland seizing the initiative of the cross-Straits situation, Lü said, "China stays focused and will make all kinds of contingency plans. If the US crosses the red line, China will definitely take firm countermeasures."

Citing one former US official, the FT report noted that sending the delegation to Taipei right after the election was a "risky move that could backfire."

Diao Daming, an expert on US studies at the Renmin University of China in Beijing, told the Global Times on Thursday that disclosing the planning of the trip ahead of the Taiwan regional leader election may suggest that the US believes that whoever takes office can be used by the White House to implement the US' "Indo-Pacific" strategy.

"If secessionist Lai Ching-te is elected, it will carry out more risk management, and if KMT's Hou Yu-ih is elected, the US will hold him back from getting too close with the mainland," he explained.

But Washington should be aware that if there is any reaction from the Chinese side, it is the result of US actions, said Diao, "Instead of being concerned about the China's countermeasures, the US should follow through on its promise [on Taiwan question]."

The US move also came amid recent increased interactions between China and US to stabilize strained ties.

Liu Jianchao, head of the International Department of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee, visited the US this week, urging it to abide by its commitment to not support "Taiwan independence."

At the Carter Center Forum commemorating the 45th anniversary of the establishment of China-US diplomatic relations on Tuesday, Xie Feng, Chinese Ambassador to the US, reiterated that the Taiwan question is the most important and sensitive question in China-US relations.

China hopes to maintain stability in the Taiwan Straits and does not want to see a conflict between China and the US over the Taiwan question, but the premise is that the US cannot cross the red line, otherwise China will definitely respond in a "tit for tat" manner, Lü said

China's communication with the US on the Taiwan question is entirely a manifestation of goodwill,Lü said,"If one day China no longer talks about the Taiwan question with the US, it means that China does not consider Washington to be a factor, then the situation will be irreversible."