Aneil Agrawal unites math and mess

Aneil Agrawal, his rangy frame at ease on a black metal street bench, is staring into some midair memory and speaking about disgust.

“I was first exposed to the idea of theoretical biology as an undergraduate and I actually hated it,” he says. “I loved biology and I liked math — it was like two different food types that you like but the two of them together are going to be terrible.”

Since then, he has remained a fan of the two foods, and his distaste for combining them has turned into enthusiasm strong enough to build a career on. Agrawal, now a 41-year-old evolutionary geneticist at the University of Toronto, both builds mathematical descriptions of biological processes and leads what he describes as “insanely laborious” experiments with fruit flies, duckweed and microscopic aquatic animals called rotifers.

Often experimentalists venturing into theory “dabble and do some stuff, but it’s not very good,” says evolutionary biologist Mark Kirkpatrick of the University of Texas at Austin. Agrawal, however, is “one of the few people who’s doing really good theory and really good experimental work.”

Two of the themes Agrawal works on — the evolution of sex and the buildup over time of harmful mutations — are “very deep and important problems in evolutionary biology,” Kirkpatrick says. Agrawal and colleagues have made a case for a once-fringe idea: that an abundance of harmful mutations can invite even more harmful mutations. Agrawal’s work has also provided rare data to support the idea that the need to adapt to new circumstances has favored sexual over asexual reproduction. Why sexual reproduction is much more common among complex life-forms has been a long-standing puzzle in biology.

Life’s complexity appealed to Agrawal from childhood; he remembers days playing among the backyard bugs and frogs in suburban Vancouver. At first, he imagined his grown-up life out in the field, “living in a David Attenborough show.” As he grew older though, he discovered he was a lab animal: “I was more interested in being able to ask more precise questions under more controlled circumstances.”

Sally Otto, now president-elect of the Society for the Study of Evolution, met Agrawal in the 1990s when he was an undergraduate at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. He returned to Vancouver in 2003, after earning his Ph.D., to do experimental work and “beef up his ability to do theory,” she says. She cosupervised his postdoctoral effort. Agrawal “picks up theory very quickly,” Otto says. Knowing a huge amount of math to begin with is less important than having insight into what math to learn. The first alluring ideas about how to approach a puzzle often don’t work out, she says, so “there’s a certain doggedness — you have to really keep at it.”

Agrawal needed some time before he came around to theoretical biology. It disgusted him, he says, because he expected it to take the rich variety out of biology. “The reason many people, including me, were attracted to biology was because it’s not boxes and triangles,” he says. “It’s complicated and interesting.” At first he thought modeling a biological process mathematically “sterilized it.” But he eventually found that mathematical description could “help to clarify our thinking about the wonderful mess of diversity that’s out there.”

At the street bench, Agrawal muses about how he tends to “think quantitatively.” His father has a Ph.D. in engineering, but “we weren’t the kind of family that had to do math problems at the dinner table.” He laughs. “Though I do that to my own kids.” His success so far is mixed, depending in part on whether he catches his two sons, ages 10 and 7, in the right mood.

Agrawal also thinks intensely, possibly another secret to his success — he has received more than half a dozen awards and prizes, including the 2015 Steacie Prize for Natural Sciences. The bench where we’ve settled is only half a block from the conference center in Austin, where Evolution 2016, the field’s biggest meeting of the year, has hit day four of its five-day marathon. Agrawal gave one of the first talks, a smooth, perfectly timed zoom through a recent fly experiment. He is a coauthor on five more presentations, along with chairing one of the frenetic sessions where talks are compressed into five minutes. By this point, many of the 1,800 or so attendees are showing strain — wearing name tags wrong side frontward, snoring open-mouthed in hallway chairs or flailing their arms in conversations fueled by way too much caffeine. Agrawal, however, seems relaxed, listening quietly, staring off in thought, speaking in quiet bursts. This guy can focus.

One of his early theory papers studied mutation accumulation. Previous work had suggested that microbes in stressful environments, compared with microbes lapped in luxury, are more likely to make mistakes in copying genes that then get passed on to the next generation. Agrawal wondered whether cells that are stressed for another reason — an already heavy burden of harmful mutations — would likewise be more inclined to build up additional mutations. He calls this scenario “a spiral of doom.”

The idea intrigued him because he suspected that sexual reproduction would do a better job of purging these mutations than asexual reproduction. “What I found in doing the theory was that I was exactly wrong,” he says. The sexual populations would end up with more, not fewer, mutations.

Though the theory part of the paper turned out well, the journal Genetics rejected it — there was hardly any experimental evidence that the scenario would arise in the real world.

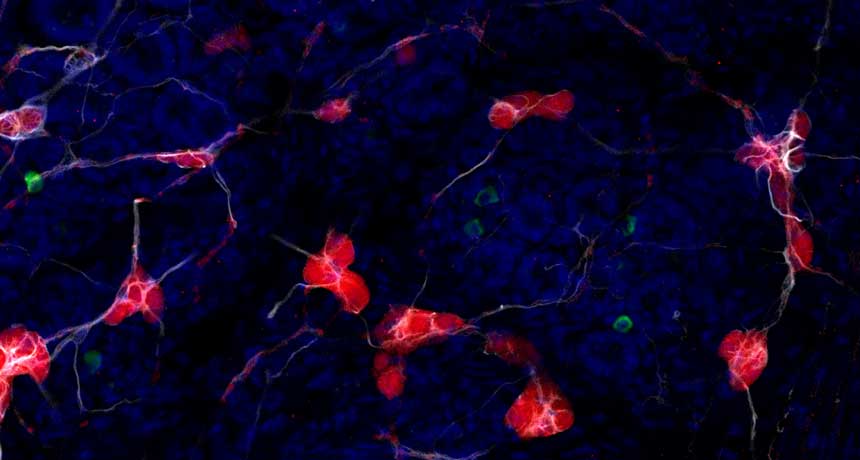

Agrawal published the paper elsewhere in 2002 and, when he began setting up his own lab at the University of Toronto, he returned to the idea. In the years since, he and colleagues have published a string of papers adding evidence to the argument. They have found, for example, that fruit flies burdened with misbegotten genes lag in growth and struggle to keep their DNA in good repair. The idea is no longer airy speculation, says Charles Baer, who’s checking for mutation accumulation in nematodes at the University of Florida in Gainesville.

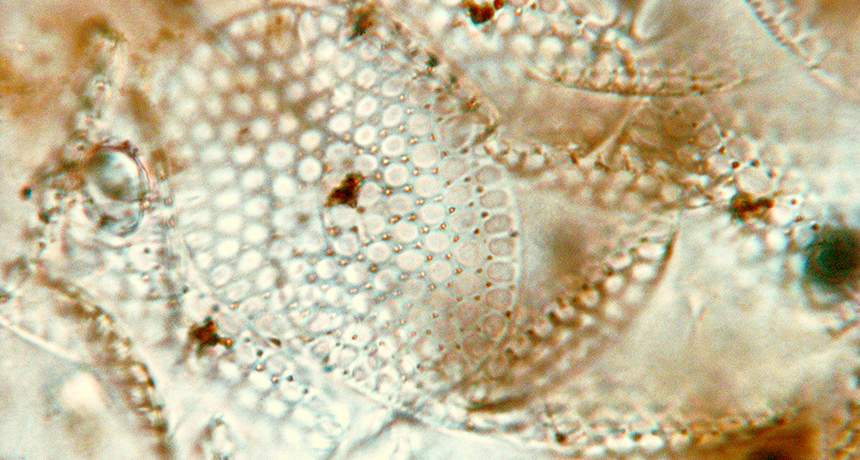

Chrissy Spencer, a postdoc during the early years of Agrawal’s mutation studies, points out that a vital skill of a good experimentalist is just knowing intuitively whether a species is right for a certain kind of test. Agrawal has that knack, for better and for worse. For some studies on the evolution of sex, Agrawal eventually turned to rotifers. The stubby little cylinders with a circlet of hairy projections around their mouths can reproduce either sexually or asexually, so they’re great for testing what factors favor one over the other. Rotifers, however, are also “finicky,” he says. His students have cared for them, sometimes for months, only to have them all die for no discernible reason, sometimes before generating any data.

Having the practitioner’s inside view of experiments and theory may help Agrawal, but it also has its costs. “There are better theoreticians out there and there are better experimentalists,” he says, and he wishes at times that he was more solidly in one camp or the other. He pauses and then, a biologist to the core, says: “That’s my niche.”