Immune cells play surprising role in steady heartbeat

Immune system cells may help your heart keep the beat. These cells, called macrophages, usually protect the body from invading pathogens. But a new study published April 20 in Cell shows that in mice, the immune cells help electricity flow between muscle cells to keep the organ pumping.

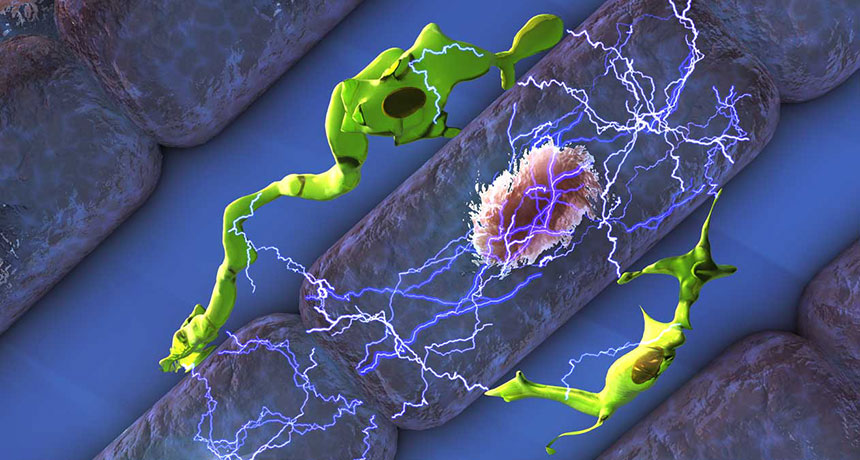

Macrophages squeeze in between heart muscle cells, called cardiomyocytes. These muscle cells rhythmically contract in response to electrical signals, pumping blood through the heart. By “plugging in” to the cardiomyocytes, macrophages help the heart cells receive the signals and stay on beat.

Researchers have known for a couple of years that macrophages live in healthy heart tissue. But their specific functions “were still very much a mystery,” says Edward Thorp, an immunologist at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. He calls the study’s conclusion that macrophages electrically couple with cardiomyocytes “paradigm shifting.” It highlights “the functional diversity and physiologic importance of macrophages, beyond their role in host defense,” Thorp says.

Matthias Nahrendorf, a cell biologist at Harvard Medical School, stumbled onto this electrifying find by accident.

Curious about how macrophages impact the heart, he tried to perform a cardiac MRI on a mouse genetically engineered to not have the immune cells. But the rodent’s heartbeat was too slow and irregular to perform the scan.

These symptoms pointed to a problem in the mouse’s atrioventricular node, a bundle of muscle fibers that electrically connects the upper and lower chambers of the heart. Humans with AV node irregularities may need a pacemaker to keep their heart beating in time. In healthy mice, researchers discovered macrophages concentrated in the AV node, but what the cells were doing there was unknown.

Isolating a heart macrophage and testing it for electrical activity didn’t solve the mystery. But when the researchers coupled a macrophage with a cardiomyocyte, the two cells began communicating electrically. That’s important, because the heart muscle cells contract thanks to electrical signals.

Cardiomyocytes have an imbalance of ions. While in the resting state, there are more positive ions outside the cell than inside, but when a cardiomyocyte receives an electrical signal from a neighboring heart cell, that distribution switches. This momentary change causes the cell to contract and send the signal on to the next cardiomyocyte.

Scientists previously thought that cardiomyocytes were capable of this electrical shift, called depolarization, on their own. But Nahrendorf and his team found that macrophages aid in the process. Using a protein, a macrophage hooks up to a cardiomyocyte. This protein directly connects the inside of these cells to each other, allowing macrophages to transfer positive charges, giving cardiomyocytes a boost kind of like with a jumper cable. This makes it easier for the heart cells to depolarize and trigger the heart contraction, Nahrendorf says.

“With the help of the macrophages, the conduction system becomes more reliable, and it is able to conduct faster,” he says.

Nahrendorf and colleagues found macrophages within the AV node in human hearts as well but don’t know if the cells play the same role in people. The next step is to confirm that role and explore whether or not the immune cells could be behind heart problems like arrhythmia, says Nahrendorf.